The Watts Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice |

In September 1887 the Victorian artist George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) wrote a letter to The Times newspaper entitled ‘Another Jubilee Suggestion’. In this letter, he put forward a plan to celebrate Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee by erecting a monument to commemorate ‘heroism in every-day life’. On the 30th July 1900, this idea was eventually realised with the unveiling of his Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice, situated in Postman’s Park in the City of London.

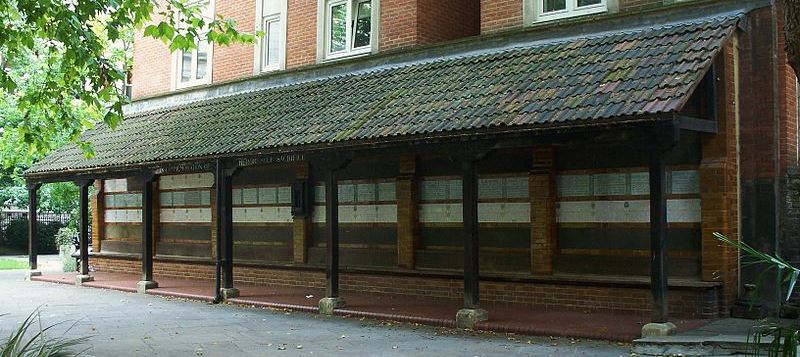

The monument consists of a modest wooden cloister, sheltering a short stretch of wall upon which are fixed fifty-four memorial tablets commemorating sixty-two individuals, men, women and children, each of whom lost their life while attempting to save another. The earliest case featured is that of Sarah Smith, a pantomime artist who died in 1863 and the latest is Leigh Pitt who drowned in 2007. The youngest individual commemorated is eight-year-old Henry Bristow; the oldest, sixty-one-year-old Daniel Pemberton.

A full and detailed history of the conception and development of the Watts Memorial and an examination of the role played by George Frederic Watts can be found in, Postman’s Park: The Watts Memorial to Heroic-Self Sacrifice by John Price which is available online from Amazon UK

FAQ

The purpose of the book, Heroes of Postman's Park: Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Victorian London is to address those curiosities and to reveal the full stories behind the everyday lives and untimely deaths of those commemorated.

A full and detailed history of the conception and development of the Watts Memorial and an examination of the role played by George Frederic Watts can be found in, Postman’s Park: The Watts Memorial to Heroic-Self Sacrifice by John Price which is available online from Amazon UK

A detailed history and analysis of the origins and development of the idea of 'everyday' heroism can be found in Everyday Heroism: Victorian Constructions of the Heroic Civilian by John Price, published by Bloomsbury (2014) and available from Amazon UK